Budget 2025 is no austerity budget, that’s for sure. Government spending remains high, revenue expectations are weak, and massive new capital outlays for defence, infrastructure and other major initiatives mean that Ottawa will need to borrow an additional $320 billion over the next five years alone. One of the key fiscal guardrails the previous government had actually kept to—a declining debt-to-GDP ratio—will be broken.

By 2030, the federal government expects to owe over $1.5 trillion dollars in debt. That’s trillion with a “T”.

Yet the budget insists that “Canada’s strong fiscal position enables us to respond to global challenges” touting Canada’s net debt-to-GDP ratio to be the lowest in the G7, even including the debt of other orders of government.

So should we be alarmed, or are we actually doing alright?

When it comes to debt, what matters most isn’t the total amount, it’s the cost of borrowing. Think of buying a car. You don’t have to pay thousands of dollars all upfront but you do need to be able to make your monthly payment. And on that front, Canada’s in decent shape.

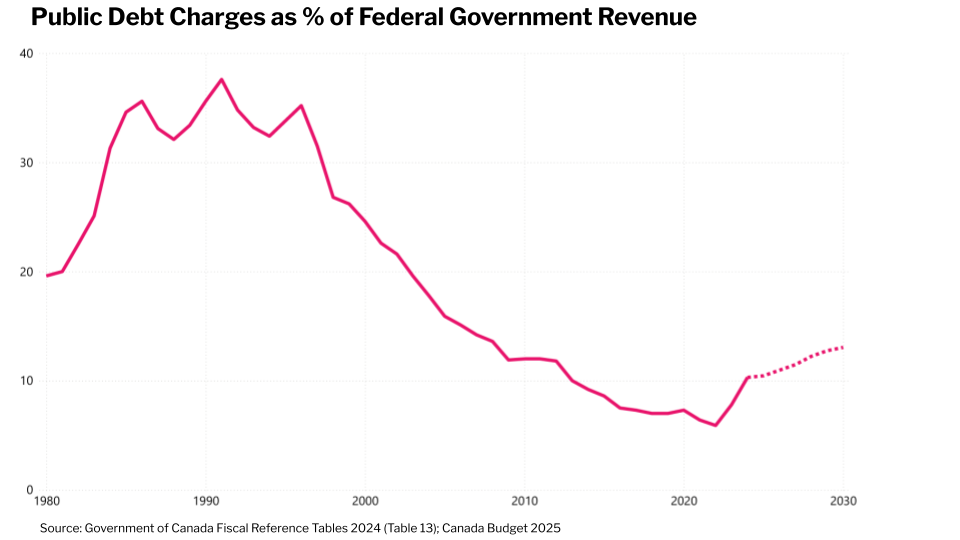

The amount the federal government pays to manage its debt is low by historical standards, totaling around 1.7% of GDP or roughly 10% of government revenues. That’s up from the historic low of 5.9% in 2021 but far behind the peaks of 35% in the 1980s and 1990s, and is still relatively low compared to other countries.

In other words, Canada’s debt is big, but it’s not necessarily unmanageable.

What keeps it so is that historically low interest rates make borrowing much cheaper than it was back in the 1980s and 1990s. Plus, most of Canada’s debt is in the form of long-term, fixed-rate bonds. So even if interest rates rise, only new borrowing would be affected; the cost of existing debt would stay the same.

Still, Canada cannot afford to throw caution to the wind. The share of revenue that will be gobbled up by debt servicing costs is projected to rise from 10% to 13% over the next five years. For things to stay under control, Canada is counting on interest rates remaining relatively moderate and stable. The budget makes this clear: if interest rates are 1% point higher than expected—a real possibility given uncertainty around long-term rates—the debt-to-GDP ratio would jump from 37.2% to 48.5% by 2055.

Bond markets globally are already hinting at concern over the amount of debt governments have taken on, with longer-term rates climbing as investors sense more risk. If confidence in Canada’s ability to repay falters, borrowing could become significantly more expensive.

Have an idea for our next EconMinute? Email us at media@businesscouncilab.com.